____________________________________________________________________________

…. As seen in the Italy Trip in April 2005 for Ken & Harriet Aitken ….. see the photos and details below.

___________________________________________________________________________

Note: I would like to share with you through these few words, photographs, and hyperlinked websites, a 3 Dimensional experience as though you were actually there with us. Click on any photograph and it should enlarge to different sizes….. at least half screen or size full screen. It will be clearer in detail than the photo on the post. It will be as if you were really there looking at the actual scene. You are an armchair traveler with us.

If you would also like to see the post in a larger or smaller size, I suggest you follow this procedure: If you right-handed, with your left hand, press down continuously on the Control Function Key with your left hand and with your right hand, move the little cursor wheel either forwards or backward to make the text in the post larger or smaller.

____________________________________________________________________________

An ancient street in hand-cut flagstones. The pedestrian walkway is on the right-hand side in smaller stone flagging.

___________________________________________________

The Map of Present Rome

____________________________________________________________________________

Pantheon …. See the website on the Pantheon here ….

Exterior Overview

Photo, Interior view

Photo Interior view

Dome interior

Dome interior at floor level.

Interior, oculus, and sunbeam. The oculus is the circular opening at the apex of the dome.

______________________________________________________________________

Stadium Of Domitian on the Palatine Hill ….. see the website here

Private hunts, games, and fights were held for Domitian (Roman Emperor from 51 to 96 AD) in this stadium. He had a passion for sport and implemented the Capitoline Games in 86 AD which was similar to the Olympic Games. Held every four years, the games included various athletic events and chariot races. Gladiator fights, including ones between female and dwarf gladiators, were also held. His private box can be seen in the lower right corner of the photo. Columns ran the entire length of this stadium. (wikipedia.org)

and also Images for Stadium Of Domitian

___________________________________________________________________________

Aurelian Walls

The wall was initiated under the emperor Aurelian in the 3rd century AD. Punctuated by a series of towers the section between the Porta Latina and Porta San Sebastiano is interesting.

See the website: http://roma.andreapollett.com/S4/aurel12.htm

History (Wickapedia.org)

By the third century AD, the boundaries of Rome had grown far beyond the area enclosed by the old Servian Wall, built during the Republican period in the late 4th century BC. Rome had remained unfortified during the subsequent centuries of expansion and consolidation due to a lack of hostile threats against the city. The citizens of Rome took great pride in knowing that Rome required no fortifications because of the stability brought by the Pax Romana and the protection of the Roman Army. However, the need for updated defenses became acute during the crisis of the Third Century, when barbarian tribes flooded through the Germanic frontier and the Roman Army struggled to stop them. In 270, the barbarian Juthungi and Vandals invaded northern Italy, inflicting a severe defeat on the Romans at Placentia (modern Piacenza) before eventually being driven back. Further trouble broke out in Rome itself in the summer of 271 when the mint workers rose in rebellion. Several thousand people died in the fierce fighting that resulted.

Aurelian’s construction of the walls as an emergency measure was a reaction to the barbarian invasion of 270; the historian Aurelius Victor states explicitly that the project aimed to alleviate the city’s vulnerability. It may also have been intended to send a political signal as a statement that Aurelian trusted that the people of Rome would remain loyal, as well as serving as a public declaration of the emperor’s firm hold on power. The construction of the walls was by far the largest building project that had taken place in Rome for many decades, and their construction was a concrete statement of the continued strength of Rome. The construction project was unusually left to the citizens themselves to complete as Aurelian could not afford to spare a single legionary for the project. The root of this unorthodox practice was due to the imminent barbarian threat coupled with the wavering strength of the military as a whole due to being subject to years of bloody civil war, famine, and the Plague of Cyprian.

The walls were built in the short time of only five years, though Aurelian himself died before the completion of the project. Progress was accelerated, and money saved, by incorporating existing buildings into the structure. These included the Amphitheatrum Castrense, the Castra Praetoria, the Pyramid of Cestius, and even a section of the Aqua Claudia aqueduct near the Porta Maggiore. As much as a sixth of the walls is estimated to have been composed of pre-existing structures. An area behind the walls was cleared and sentry passages were built to enable it to be reinforced quickly in an emergency.

The actual effectiveness of the wall is disputable, given the relatively small size of the city’s garrison. The entire combined strength of the Praetorian Guard, cohortes urbanae, and vigiles of Rome was only about 25,000 men – far too few to defend the circuit adequately. However, the military intention of the wall was not to withstand prolonged siege warfare; it was not common for the barbarian armies to besiege cities, as they were insufficiently equipped and provisioned for such a task. Instead, they carried out hit-and-run raids against ill-defended targets. The wall was a deterrent against such tactics.

Parts of the wall were doubled in height by Maxentius, who also improved the watch-towers. In 401, under Honorius, the walls and the gates were improved. At this time, the Tomb of Hadrian across the Tiber was incorporated as a fortress in the city defenses.

_____________________________________________________________________________

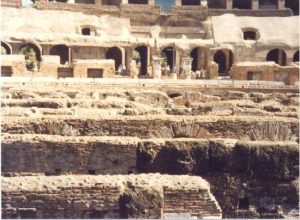

Colosseum (or Coliseum as alternative spelling) ….

….. see the Map of Present Rome above….

From Rome.info > Roman Colosseum, Coliseum of Rome

The Roman Colosseum or Coliseum, originally known as the Flavian Amphitheatre, was commissioned in AD 72 by Emperor Vespasian. It was completed by his son, Titus, in 80, with later improvements by Domitian.

The Colosseum is located just east of the Roman Forum and was built to a practical design, with its 80 arched entrances allowing easy access to 55,000 spectators, who were seated according to rank. The Colosseum is huge, an ellipse 188m long, and 156 wide. Originally 240 masts were attached to stone corbels on the 4th level.

Just outside the Colosseum is the Arch of Constantine (Arco di Costantino), a 25m high monument built in AD315 to mark the victory of Constantine over Maxentius at Pons Milvus.

Vespasian ordered the Colosseum to be built on the site of Nero’s palace, the Domus Aurea, to dissociate himself from the hated tyrant.

His aim was to gain popularity by staging deadly combats of gladiators and wild animal fights for public viewing. The massacre was on a huge scale: at inaugural games in AD 80, over 9,000 wild animals were killed. See the note below on the life of gladiators on the website above.

____________________________________________________________________________

See the wonderful website: Roman Gladiator .….

https://www.ancient.eu/gladiator/

____________________________________________________________________________

From:

Learn About the Great Ancient Stadiums and Venues

The Colosseum was completed in 80 AD under the Roman emperor Titus. It’s a three-tiered stadium that stood 157 feet tall. It featured 80 entrances and have seated around fifty thousand people. This stadium is considered to be one of the greatest works of Roman architecture and engineering.

Back in the ancient times, gladiatorial combat, animal hunts, and simulated naval battles were held in the Colosseum. In 240 AD, during a seven-day festival, there were 2,000 gladiators and hundreds of animals that died in this stadium.

The Colosseum was closed in 523 AD. During that time, an estimated number of more than a million animals and more than five hundred thousand people have died there.

__________________________________________________________________________

…. Walking into the Colosseum ….

A road in flagged stone pieces near the Colosseum.

The pedestrian walkway is on the right-hand side in smaller stone flagging.

A modern footpath has been built on the left-hand side of the road

See the website: Images for Coliseum

…. Street stone flagging near the Colosseum …..

Gladiators:

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gladiator

Gladiators were usually recruited from criminals, slaves (especially captured fugitives), and prisoners of war. Criminals, having lost their civil rights and slaves and prisoners of war having none, had no choice about becoming a gladiator, if they had the physical and emotional make-up necessary for the profession. Some free-born men, however, although they had not lost their civil rights, voluntarily chose the profession and bound themselves body and soul to the owner of a gladiatorial troupe (lanista) by swearing an oath “to endure branding, chains, flogging or death by the sword” and to do whatever the master ordered (Petronius Sat. 117.5). It has been estimated that by the end of the Republic, about half of the gladiators were volunteers (auctorati), who took on the status of a slave for an agreed-upon period of time.

But why would a free man want to become a gladiator? When he took the gladiator’s oath, he agreed to be treated as a slave and suffered the ultimate social disgrace (infamia). Seneca describes the oath as “most shameful” (Ep. 37.1-2). As unattractive as this may sound to us, there were advantages. The candidate’s life took on a new meaning. He became a member of a cohesive group that was known for its courage, good morale, and absolute fidelity to its master to the point of death. His life became a model of military discipline and through courageous behavior, he was also now capable of achieving honour similar to that enjoyed by Roman soldiers on the battlefield.

There were other advantages. For example, an aristocrat who had suffered a great financial setback in a lawsuit or who had squandered his inheritance would find it extremely difficult to make a living. After all, he had spent his life living on inherited wealth and was not used to working for a living. He could enter the army or become a school teacher, or take up a life of crime as a bandit. In comparison with these occupations, a career as a gladiator might seem more attractive. He would not fight more than 2 or 3 times a year and would have a chance at fame and wealth (with which they could buy their freedom), employing those military skills that were appropriate to the citizen-soldier. In the arena, the volunteer gladiator could indulge his fantasy of military glory and fame before an admiring crowd. As a gladiator, he could achieve the kind of public adulation that modern athletes enjoy today.

Donald Kyle points out other practical advantages of the gladiator’s life:

The living conditions of gladiators were harsh but, as profitable investments, they perhaps lived better than many commoners in terms of food, housing, and medical attention. New or undisciplined men were shackled and unattended only in the bathroom, but trained gladiators were not always bound, imprisoned, or even confined to barracks.

The gladiator was often the object of female adoration. This is clear in the following graffiti from Pompeii (CIL 4.4397 and 4356):

Celadus the Thracian, three times victor and three times crowned, adored by young girls.

Crescens the nocturnal netter (Lucretius) of young girls.

Apparently, aristocratic matrons also found gladiators especially attractive. Juvenal tells us of a senator’s wife named Eppia, who ran off with her gladiator lover to Egypt (6.82 ff.). Of course, the free man would have to weigh these advantages with the risk of an early, violent death and the status of a slave. But perhaps that would have been better than becoming a schoolteacher!

Even women fought as gladiators, although rarely. Aristocratic women and men fought as entertainment for Nero in 63 AD. Domitian had women fight by torchlight and on another occasion had women fight with dwarves. Romans loved these exotic gladiatorial combats. In Petronius, one character looks forward to the appearance of a female gladiator called an essedaria, she (Sat. 45.7.2). The banning of female gladiators by Septimius Severus (late second, early 3rd cent. AD) suggests that women were taking up this occupation in alarming numbers.

It should also be noted that some emperors were swept away by gladiator mania, such as Caligula and Commodus (late second century AD). Both of these emperors actually appeared in the arena as gladiators, no doubt with opponents who were careful to inflict no harm. Both of these emperors were mentally unstable and apparently felt no inhibitions in indulging their gladiatorial fantasies. But gladiator mania affected not only the mentally unbalanced. At least seven other emperors of sound mind (including Titus and Hadrian) either practiced as gladiators or fought in gladiatorial contests.

Gladiators were owned by a person called a lanista and were trained in the lanista’s school (ludus). Gladiatorial combat was as much a science as modern boxing (Sen. Ep. 22.1). The training involved the learning of a series of figures, which were broken down into various phases. Sometimes fans complained that a gladiator fought too mechanically, according to the numbers. In the early Empire, there were four major gladiatorial schools, but by this time, the training of gladiators had been taken over by the state. No doubt it was thought too dangerous to allow private citizens to own and train gladiators, who could be easily turned into a private army for revolutionary purposes. Therefore, with very few exceptions, gladiators were under the control and ownership of the emperor, although the lantista continued to train and own gladiators outside of Rome. The lanista made a profit by renting or selling the troupe. This was a very lucrative business, but on the other hand, he was viewed as among the lowest of the low on the social scale. The objection was that these men derived their whole income from treating human beings like animals. Auguet writes:

In the eyes of the Romans, he was regarded as both a butcher and a pimp. He played the role of scapegoat; it was upon him that society cast all the scorn and contempt aroused by an institution that reduced men to the status of merchandise or cattle.

By a rather tortured rationalization, an upper-class citizen could own and maintain his own troupe and even hire them out without suffering the scorn of his fellow aristocrats. The saving factor was that the citizen was a dabbler and not a professional: his main source of income did not derive from his ownership of gladiators.

____________________________________________________________

Roman Forum

The forum was the center of political, commercial, and judicial life in ancient Rome. The largest buildings were the basilicas, where legal cases were heard. According to the playwright Plautus, the area teemed with “lawyers and litigants, bankers and brokers, shopkeepers and strumpets, good-for-nothings waiting for a tip from the rich”.

As Rome’s population boomed, the forum became too small. In 46 BC Julius Caesar built a new one, setting a precedent that was followed by emperors from Augustus to Trajan. As well as the Imperial Forum, emperors also erected triumphal arches to themselves, and just to the east Vespasian built the Colosseum, center of entertainment after the business of the day.

The formation of the Forum valley was to the erosion of a bank of volcanic tufa by a stream named the Velabrum, which meandered between the Palatine and Capitoline hills toward the Tiber.

Used as a necropolis in the Iron Age (10th to 9th century BC), this marshy area was drained at the beginning of the rule of the Etruscan kings, when Tarquinius Priscus is said to have channeled the waters of the Velabrum in order to implement a series of public works, the most important being the city’s huge sewer, the cloaca maxima.

Rome then began to develop on this site, which remained its political, administrative and religious center until the end of the Republican period.

During the Middle Ages, when the population gradually settled in the Campus Martius, the Forum – although strew with debris – came to be used as grazing for cattle and acquired the name of Campo Vaccino (“the cattle field”). It was not until the 19th century that the archaeologists began to unearth the half-buried ruins, digging sometimes as deep as 65 feet.

_________________________________________________________________

____________________________________________________________

The Palantino Area

…… the Suburban Area where Romans lived in the First Century …..

From this website: Palatino – Lonely Planet

Sandwiched between the Roman Forum and the Circo Massimo, the Palatino (Palatine Hill) is an atmospheric area of towering pine trees, majestic ruins and memorable views. It was here that Romulus supposedly founded the city in 753 BC and Rome’s emperors lived in unabashed luxury. Look out for the Stadio (stadium), the ruins of the Domus Flavia (imperial palace), and grandstand views over the Roman Forum from the Orti Farnesiani.

Roman myth holds that Romulus established Rome on the Palatino after he’d killed his twin Remus in a fit of anger. Archaeological evidence clearly can’t prove this, but it has dated human habitation here to the 8th century BC.

As the most central of Rome’s seven hills, and because it was close to the Roman Forum, the Palatino was the ancient city’s most exclusive neighborhood. The emperor Augustus lived here all his life and successive emperors built increasingly opulent palaces. But after Rome’s decline, it fell into disrepair, and in the Middle Ages, churches and castles were built over the ruins. During the Renaissance, members of wealthy families established gardens on the hill.

Most of the Palatino as it appears today is covered by the ruins of Emperor Domitian’s vast complex, which served as the main imperial palace for 300 years. Divided into the Domus Flavia, Domus Augustana, and a stadio, it was built in the 1st century AD.

On entering the complex from Via di San Gregorio, head uphill until you come to the first recognizable construction, the stadio. This sunken area, which was part of the main imperial palace, was probably used by the emperors for private games and events. To the southeast of the stadium are the remains of a complex built by Septimius Severus, comprising baths (the Terme di Settimio Severo ) and a palace (the Domus Severiana ) where, if they’re open, you can visit the Arcate Severiane, a series of arches built to facilitate further development.

On the other side of the stadio are the ruins of the huge Domus Augustana, the emperor’s private quarters in the imperial palace. It was built on two levels, with rooms leading off a peristilio (peristyle or porticoed courtyard) on each floor. You can’t get down to the lower level, but from above you can see the basin of a big, square fountain and beyond it rooms that were originally paved with colored marble. In 2007 a mosaic-covered vaulted cavern was discovered more than 15m beneath the Domus. Some claim this is the Lupercale, a cave believed by ancient Romans to be where Romulus and Remus were suckled by a wolf.

The grey building next to the Domus Augustana houses the Museo Palatino, a small museum dedicated to the history of the area. Archaeological artifacts on show include a beautiful 1st-century bronze, the Erma di Canefora, and a celebrated 3rd-century graffito depicting a man with a donkey’s head on the cross.

North of the museum is the Domus Flavia, the public part of the palace complex. This was centered on a grand columned peristyle – the grassy area you see with the base of an octagonal fountain – off which the main halls led. To the north was the emperor’s throne room; to the west, a second big hall that the emperor used to meet his advisers; and to the south, a large banqueting hall, the triclinium.

Near the Domus, the Casa di Augusto, Augustus’ private residence, features some superb frescoes in vivid reds, yellows, and blues. Further illustrations adorn the Casa di Livia, the separate home of Augustus’ wife Livia. Built around an atrium leading onto what were once reception rooms, the Casa is frescoed with depictions of mythological scenes, landscapes, fruits, and flowers.

Behind the Casa di Augusto are the Capanne Romulee, where it’s thought Romulus and Remus were brought up by a local shepherd called Faustulus.

Northeast of the Casa di Livia lies the cryptoporticus, a 128m tunnel where Caligula was thought to have been murdered, and which Nero later used to connect his Domus Aurea with the Palatino. Lit by a series of windows, it’s now used to stage temporary exhibitions.

The area west of this was once Tiberius’ palace, the Domus Tiberiana, but is now the site of the 16th-century Orti Farnesiani, one of Europe’s earliest botanical gardens. A viewing balcony at the northern end of the garden commands breathtaking views over the Roman Forum.

Also see this wonderful website:

Rome’s Palatine Hill: The Complete Guide

…. An open sewer and drainage channel …

See the website: Images for Palatino Rome

_____________________________________________________________________________

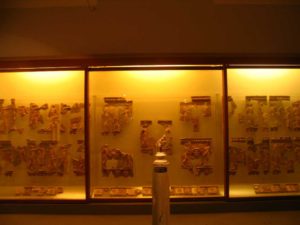

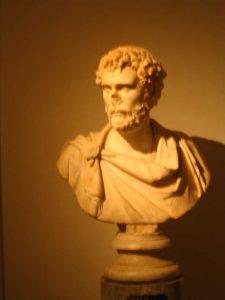

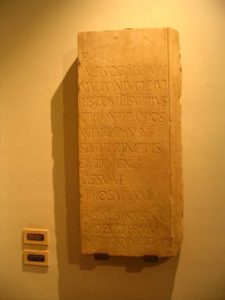

Palatine Museum

The Palatine Museum HISTORY

The Palatine Museum (Museo Palatino) on Rome’s Palatine Hill houses a collection of finds from this incredible archaeological site.

With artifacts dating back as far as the Middle Palaeolithic era, the Palatine Museum offers a good overview of the area considered to be the birthplace of Rome.

The main exhibits at the Palatine Museum date back to ancient Rome, particularly between the first and fourth centuries AD, when the Palatine Hill was the best address in the city and home to Rome’s emperors.

___________________________________________________________________________

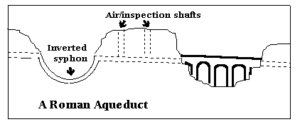

Roman Aqueducts

Ancient Rome had eleven major aqueducts, built between 312 B.C. (AquaAppia) and 226 A.D. (Aqua Alexandrina); the longest (Anio Novus) was 59 miles long. It has been calculated that in imperial times when the city’s population was well over a million, the distribution system was able to provide over one cubic meter of water per day for each inhabitant: more than we are accustomed to using nowadays.

For most of their length, the early aqueducts were simply channels bored through the rock, from the water intake in the hills almost to the distribution cistern in Rome. The depth of the channel below ground varied so as to maintain a constant, very shallow gradient (less than 1/200) throughout the length of the aqueduct; vertical shafts were bored at intervals to provide ventilation and access. Only in the final stretches was the conduit raised on arches, to give a sufficient head for distribution of the water within the city.

Aqueduct to supply water to Rome …..

In order to keep the gradient constant, the aqueducts took a roundabout route, following the contours of the land and heading along spurs which led towards Rome. As time went on, Roman engineers became more daring in the construction of high arches to support the conduits across valleys and plains and some of the later aqueducts were as much as 27 meters (about 100 feet) above ground level in places. Closed pipes were occasionally used to cross valleys by the “inverted siphon” method: the pressure forced the water down and up again on the other side, to a level slightly lower than before. But this system was costly, as it required lead pipes (lead had to be imported from Spain or Great Britain) and it was difficult to make joints strong enough to withstand the pressure; so arches were far more common.

Except where closed pipes were used, the channel in which the water flowed was just over three feet wide and about six feet high, to allow workers to walk throughout its length – when the water supply had been cut off – for inspection and maintenance. Where the aqueduct went through impermeable rock it was not lined, but where the rock was porous, and where the conduit ran on arches, a layer of impermeable concrete was applied to form a waterproof lining (opus signinum).

Every now and then there was a sedimentation tank, where the flow of water slowed down and impurities were deposited. Where two or more conduits ran near one another, as was common in later times, there were places in which water could be exchanged between them, either to increase the flow of an aqueduct carrying little water or so that one of the conduits could be emptied for maintenance and repair.

Aqua Claudia was started by Caligula (AD 12 – 41) and officially finished by Claudius (10 BC-AD 54), the Aqua Claudia was constructed between 38 and 52 AD. The date of completion is given in an inscription at Porta Maggiore, but Tacitus (2.13) suggests that the aqueduct was in use by 47 AD. It was fairly common practice to begin using an aqueduct before construction was completed. Caligula ordered its construction because the seven existing aqueducts were by now inadequate due to the demand for water from consumption and utilities such as the baths. It is on account of its massive arches that the Claudia is one of Rome’s most visually impressive aqueducts.

See this website: Aqua Claudia

When the water reached Rome, it flowed into huge cisterns (castella), situated on high ground, from which it was distributed through lead pipes to the different areas of the city. Part of the water was for the emperor’s use, part of it was sold to rich citizens, who – for a price – could have it piped to their private villas, but much of it was available to the populace through a network of public fountains, which were located at crossroads throughout the city, never more than 100 meters apart. Enormous amounts of water went to supply the numerous bath complexes, such as the Baths of Caracalla.

For centuries, an army of laborers was constantly at work, under the supervision of the curator aquarum, extending and repairing the water system. But in the 6th century A.D., as the power of the Empire began to decline, the Goths besieged Rome and cut almost all the aqueducts leading into the city. (The only one that continued to function was that of the Aqua Virgo, which ran entirely underground.) One or two were later restored and were used during the Middle Ages, but most of the population had to resort to the Tiber as the only source of water: it is for this reason that the medieval buildings of Rome lie almost exclusively in the two great bends of the river, the Campo Marzio and Trastevere. It was not until Renaissance times that the Eternal City was once again provided with aqueducts and fountains.

_____________________________________________________

See the next post: Trip 3: ITALY HOLIDAY in ….. POMPEII = Post 4